If you’ve found it hard to concentrate for long periods of time during the coronavirus pandemic, never fear — here are 29 books that might yet make you want to read again.

Before she was a best-selling novelist, Brit Bennett was gaining viral fame for her searing critical essays about race and privilege in America, like her Jezebel piece “I Don’t Know What to Do With Good White People.” Her second novel (after 2016’s excellent The Mothers) is about estranged twin sisters, one of whom is secretly passing as white.

A wedding makes for a great plot device in fiction, capturing a window of time when families are forced to be together while wearing uncomfortable clothes and emotions are running high. But Parakeet contains so much more than the typical wedding narrative: it’s a surrealist rendering of an ambivalent bride and the traumas she can’t outrun no matter the occasion. Parakeet kicks off when the bride’s dead grandmother, in the form of the title bird, appears in her hotel room and craps on her wedding gown. From there the bride slides in and out of other realities as she tries to make peace with her past. As more of the bride’s memories are unfurled and dissected, her forays into other dimensions become both rational and revelatory.

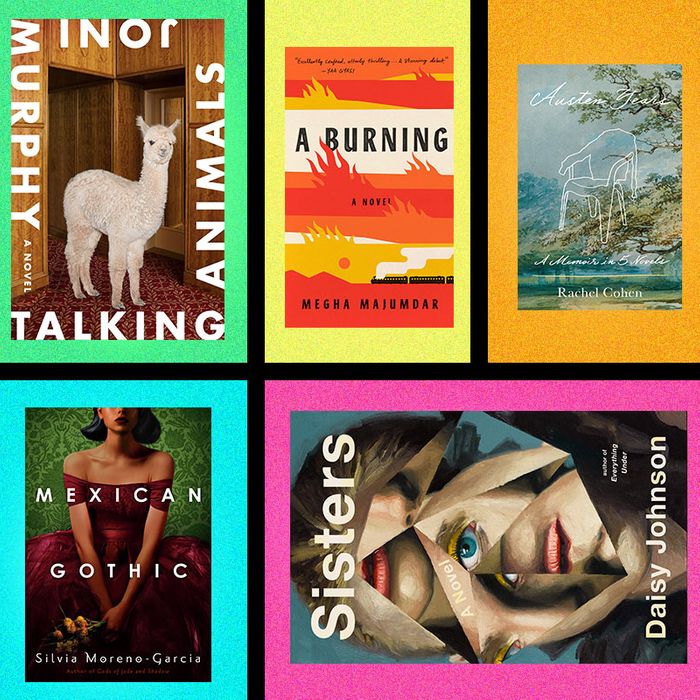

An exquisitely paced and assured debut, A Burning is so propulsive you’ll finish it faster than you can invoke the proper fire metaphor. It’s the story of Jivan, a Muslim girl on the brink of leaving the slums of Bengal when she makes one angry comment on Facebook that leads to her being falsely accused of a terrorist attack. Her alibi is the big-hearted Lovely, a Hijra (Indian trans woman) who yearns to be an actress and has plenty of her own issues with which to contend. PT Sir, Jivan’s former high school gym teacher, is a potential character witness whose own political ambitions are too outsized for him to stick his neck out for anyone. A Burning details the ways in which the severely oppressed are forced to use betrayal as a survival method, and who gets ahead and who remains collateral damage when the system is rigged.

The comparisons tossed around for Emily Temple’s debut could hardly be more tantalizing. Chloe Benjamin called it “the love child of Donna Tartt and Tana French.” Others have compared Temple to Ottessa Moshfegh and Emma Cline. The story follows a 16-year-old girl whose father has disappeared, and her efforts to trace him to a strange meditation retreat in the mountains where the leaders promise to teach the art of levitation.

Literature’s reigning queen of the profane, Ottessa Moshfegh is divisive: Readers tend to love her or hate her. If her latest novel is subtler than her most recent works, it’s just as chilling — it could be a jumping-off point for new readers. A self-contained horror story that takes place inside the mind of an alluringly unreliable narrator, the novel follows a 72-year-old widow who has moved with her dog to a large plot of land where they are seemingly at one with nature. When she finds a handwritten note that implies a murder has taken place on her property, she works to solve it as best she can. The narrator’s dark fantasies and less-than-pure thoughts work especially well if you think of Death in Her Hands as a sequel to Moshfegh’s deliciously gross and grotesque debut novel, Eileen.

Picture the spooky Victorian mansion where a Bronte heroine or a Sarah Waters character used to live, and transport it to a remote mountainside in Mexico in 1950, and you have Mexican Gothic. Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s twisty new horror novel follows vibrant heroine Noemi Taboada who leaves her life as a debutante to check on her newly married cousin, Catalina, who has been sending some alarming letters home. Catalina has married into a creepy old English family who once ran a silver mine in the neighboring village, and who now live an isolated existence in High Place, a dark and dreary estate that lacks electricity but has an appropriately misty graveyard. Is Catalina being poisoned or haunted by ghosts or has she simply gone mad from living at High Place or all of the above? Moreno-Garcia puts a new spin on a pleasantly familiar trope as Noemi learns more about her cousin’s eugenics-obsessed in-laws and their dark secrets.

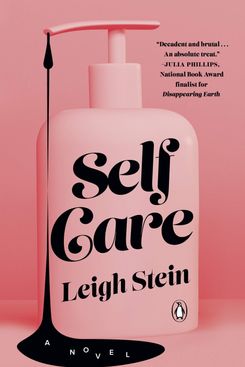

The cover of Self Care features a Pepto-pink lotion bottle, sleek and rounded for optimal millennial aesthetic satisfaction, with black bile leaking from its pump. Its both a lure — here’s more of that smooth, pretty feminism you can pay to indulge in — and an indictment of the icky tar-like bullshit women are sold every time they swipe their phones open. Stein’s story is about a wellness entrepreneur (a founder of a women’s empowerment community called “Richual”) who fires off an ill-advised swipe at a Trump daughter and faces a backlash. It’s also a brutal dissection of “Insta-worthy” culture, the unconscionable capitalistic impulses behind wellness ventures, and the farce of forced community building.

Charlie Kaufman is the rare screenwriter who is as celebrated as the directors who have brought his mind-bending scripts to the screen. Now he’s a novelist too. Antkind follows a failed film critic who stumbles across the greatest film of all time — a three-month-long, stop-motion masterpiece that took 90 years to make and has since been destroyed, save for a single frame. If you loved Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, I shouldn’t have to tell you anything else to convince you to read it. —LS

If you’re a fan of Sally Rooney novels, try Andrew Martin’s Early Work. Martin is neither female nor Irish but he scratches the same itch as Rooney, with cerebral characters and tender discoveries and enough acid to keep the thing balanced. Martin’s follow-up is a collection for short stories that explores the search for transcendence through art.

More than anything, Lynn Steger Strong’s Want is a reader’s novel, which is to say that it is rife with mentions of other novelists (Jean Rhys, Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing, Anita Brookner) and both indebted to and an homage to their work. It’s the story of Elizabeth — a want-to-be professor turned high-school teacher headed for bankruptcy with her Wall Streeter turned furniture-maker husband and their two little girls — who can’t stop herself from slipping away from her life and getting lost inside fictional worlds. Meanwhile her real world, of inertia and continual catastrophe, continues to unfold against the backdrop of our steadily unraveling country.

We live in horrifying times, so why not give in and read one of the most eagerly anticipated horror novels of the year? Stephen Graham Jones is a Blackfeet Native American author and his 20th (or so) book follows four childhood friends from the Blackfeet Nation who grew up and moved away, only to find themselves, a decade later, tracked by an entity bent on revenge, and forced to reckon with an act of youthful violence.

The Crazy Rich Asian author’s latest is an homage to E.M. Forster’s Room With a View. It follows Lucie Churchill, a half-Chinese woman amidst an identity crisis. She has always favored her white side and rejected her Asian heritage, so when she meets a man named George Zao and begins to fall for him, she adamantly tries to deny it.

Utopia Avenue is, according to Mitchell, “the strangest British band you’ve never heard of,” and the subject of this late-1960s-set, 600-page tome, which is reportedly filled with everything worth reading about — sex, psychedelia, and stardom. No word yet on whether its structure folds in on itself, like the novelist’s 2009 megahit Cloud Atlas, or returns to more linear forms of storytelling, like his 2006 bildungsroman Black Swan Green. Either way, it’ll be a publishing event and will most likely suck you right in.

“About seven years ago…” Rachel Cohen begins this tender, rigorous criticism/memoir hybrid, “Jane Austen became my only author.” She’s only very slightly exaggerating. Around the time her children were born and her father died, she began obsessively reading and rereading Austen’s novels, working through the same scenes dozens of times, dissecting the language with a nearly mathematical precision. Austen Years, much like Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch or Katharine Smyth’s All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf, intimately matches Jane’s literary interrogations — especially those about how women process the infinite varieties of grief — with tender personal sketches. The premise could turn hokey, but Cohen’s readings are invigorating, especially about her final completed, vastly under-read novel, Persuasion.

Perhaps best known for The Room, a harrowing tale about a mother and son held captive in a small room for nearly a decade, Donoghue’s latest feels even more prescient. Set in Dublin in 1918, as the city is in the grip of one of the last great pandemics, the story follows a nurse in a maternity ward over three harrowing days.

Imagine this: A child appears in your small town’s church. Its gender identity and sex are unclear. Its skin offers only the barest hints about its race. And it refuses to, or cannot, speak a word. The child is given the nickname Pew (after the place he/she is found) and taken in by a family bent on reminding the child of their charity and goodness. But the longer Pew stays, the more the town’s ancient grudges break to new mutiny. Catherine Lacey, a fiction wunderkind who writes with dynamite, has recreated herself, and our ideas about what novels can do, yet again.

A high-concept speculative adventure novel executed with intelligence and grace, Australian writer Landragin’s debut contains a story within a story within a story. Crossings is an invigorating puzzle of a book that reads like a complete, intricate work of genre-defying fiction rather than just a cool gimmick. Consisting of three separate stories you can read straight through or out of order with a secret key (a guide appears in the intro), it follows the adventures of the poet Charles Baudelaire, a Walter Benjamin-type in WWII Paris, and the crossings of their souls into different bodies. For all the Freaky Friday-ing that happens in the book, Crossings doesn’t descend into silliness. It deftly tackles both the big and small mysteries of life — including in which order one should read it.

Yiyun Li is primed for a breakout. In her brilliant and spare previous novel, Where Reasons End, a grieving mother converses with her son, whom she has lost to suicide. Must I Go covers similar themes but it’s bigger and messier and even more ambitious. In a nursing home, Lilia Liska pours through the posthumously published diaries of a former lover — she’s merely a footnote in a “great” man’s text. But Lilia’s copious annotations to the diary allow her to be the heroine of her own story. Through Lilia’s recollections Yiyun Li has crafted an epic story of a life full of regret, but also of hope and perseverance and the importance of passing down our legacies.

When former Poet Laureate of the United States Natasha Trethewey was 19, her mother was shot in the head at point-blank range and killed by Trethewey’s former stepfather. Now, 35 years later — and just after he’s been released from prison for the crime — she’s publishing her account of her childhood and the trauma that has followed her all these years. For all its heavy subject matter, Memorial Drive is crystalline. The writing is spare but always lands a direct hit. You’ll read it in an afternoon but think about it for decades to follow.

In this debut novel from Raven Leilani, set between Bushwick and suburban Jersey, Edie, a sexually precocious publishing staffer, meets and falls in …. something with Eric, a married man swiping through apps on a lark. What stands out here is Leilani’s prose (“I think to myself, You are a desirable woman. You are not a dozen gerbils in a skin casing.”), which is breathless, frantic, and reads like a Twitter wit grew legs and an IRL identity.

In a near-future world where most bird species have gone extinct, ornithologist Franny Stone is determined to follow the last flock of Arctic terns on their migration south. She convinces a fishing crew to take her on this madcap expedition and slowly reveals the story of her hellish upbringing, unconventional marriage, and the bizarre set of circumstances that led her to the end of the Earth, hoping for a glimpse of aerial beauty. Migrations is so quiet and steady you can practically hear the glaciers cracking to pieces and the shrill yelps of the circling terns.

12 years after the last Twilight installment, Stephenie Meyer has returned to gift her fans with a prequel of sorts, revisiting the beginning of Bella Swan and Edward Cullen’s iconic romance from his perspective. In a note on her website announcing the book, Meyer waxed nostalgic: “Completing Midnight Sun has brought back to me those early days of Twilight when I first met many of you. We had a lot of fun, didn’t we? Throwing proms and hanging out in hotel rooms and reading on the beach (while getting the most epic sunburns of our lives)… I hope going back to the beginning of Bella’s and Edward’s story reminds you of all that fun, too.”

Come for the cover, which depicts a thoughtful alpaca, and stay for the tale of intrigue, climate change, and metropolitan doom—all in a world without humans. Sounds nice right now!

Why does The Challenger explosion remain so vivid in our collective consciousness when other, deadlier atrocities have taken place regularly since 1986? “Our cultural calculus on what constitutes the ‘worst’ disasters must include how much publicity they get,” writes the poet Elisa Gabbert in her searing essay collection that takes place at the intersection of devastation, technology, and memory. In shattering essays, Gabbert explores if and how and why certain threats register more than others, and how even seemingly immutable facts are subject to spin from our imprecise recollections. There’s a chapter on pandemics, and yes, it is chilling.

Details are slim about the plot of Smith’s Seasonal Quartet finale. As of this writing, her final manuscript isn’t even into her publishers. But if the caliber and tenacity of the first three novels — Autumn, published in 2016; Winter, published in 2017; and Spring, published in 2018 — holds up, Summer stands to cement Smith’s legacy as a novelist who can fully adapt fiction’s forms to reflect the vertiginous sociopolitical upheavals of its time. The previous novels in the quartet, all set in mid-Brexit, mid-civil-society-renting England, have zeroed in on a remarkable May-December friendship, a family huddled together for a combative Christmas holiday, and a young girl detained in a refugee facility. They’ve all rejiggered the space-time continuum inside the contemporary novel and called for a new kind of storytelling.

We’re meant to hate the suburbs and aspire to them, all at once. The Stepford tract McMansions spawned from Levittown, the acres of pesticide-controlled overzealous green grass, the inevitable strip mall combo of Petco, HomeGoods, Best Buy, and a TGI Fridays. For all the shit we give the ‘burbs they’re also the breeding grounds for so much of the cultural discourse of the last 75 years. The Simpsons, Back to the Future, Cheever, the Columbine shooting, Ben Folds’ entire ironic oeuvre. In The Sprawl, which manages the difficult feat of being exceptionally smart and wildly fun at the same time, Jason Diamond, a suburbanite by birth and city-dweller by choice, tracks the rise, fall, degradation, and rehabilitation of those city-ringing social laboratories that kids are begging to break out of and 40-somethings are flocking to. He’ll almost make you want to leave the city behind. Almost.

When her debut novel, Everything Under, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2018, Johnson became the youngest author ever to secure the honor. Her follow up is a gothic thiller about a pair of sisters sequestered in the countryside after their mother moves them to an old family house by the shore. A novel about family facing their darkest impulses while quarantined together? Highly relatable.

This short-story collection seems likely to explore similar terrain to Cline’s eerie and lyrical bestselling debut, The Girls: the power dynamics within families, characters who sabotage themselves, acts of violence. If you’re craving something beautiful and chilling before September 1, try the first short story she ever published, which won The Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize.

We slapped our hands over our eyes reading the reviews out of Europe of Ferrante’s first novel after the conclusion of the girlhood-affirming Neapolitan quartet — how could she possibly match the piercing yearning that had characterized that series? But critics are delighting in The Lying Life of Adults, another Naples-set bildunsgroman of a disenchanted young girl on the cusp of womanhood, though this time it’s set in the 1990s among the intelligentsia.

Every editorial product is independently selected. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.

What Else Is Happening This Summer

- Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 1 +2 Forever Altered the Course of Gaming and Music

- The 8 Can’t-Miss Video Games of This Summer

- Want Is the Summer Book I Couldn’t Put Down